In summer 2024, I joined Design Research Works as a design-researcher-in-residence. The residency continued a line of inquiry I began the previous year, when I hosted a workshop at 4S – a science and technology studies (STS) conference – in Honolulu. There, I worked with STS researchers to translate their conference papers into movie-concept pitch presentations. That experiment showed how quickly complex research can be turned into speculative film concepts and raised the question of what might happen if this approach were developed further.

Alongside the practical experiment of making movie concepts with academics, the residency was also informed by an interest in how film and design intersect within research. Christopher Frayling’s [1] influential typology of research in art and design has long highlighted cinema as a productive site for thinking about forms of design research, something he later expanded in his talks on production design [2].

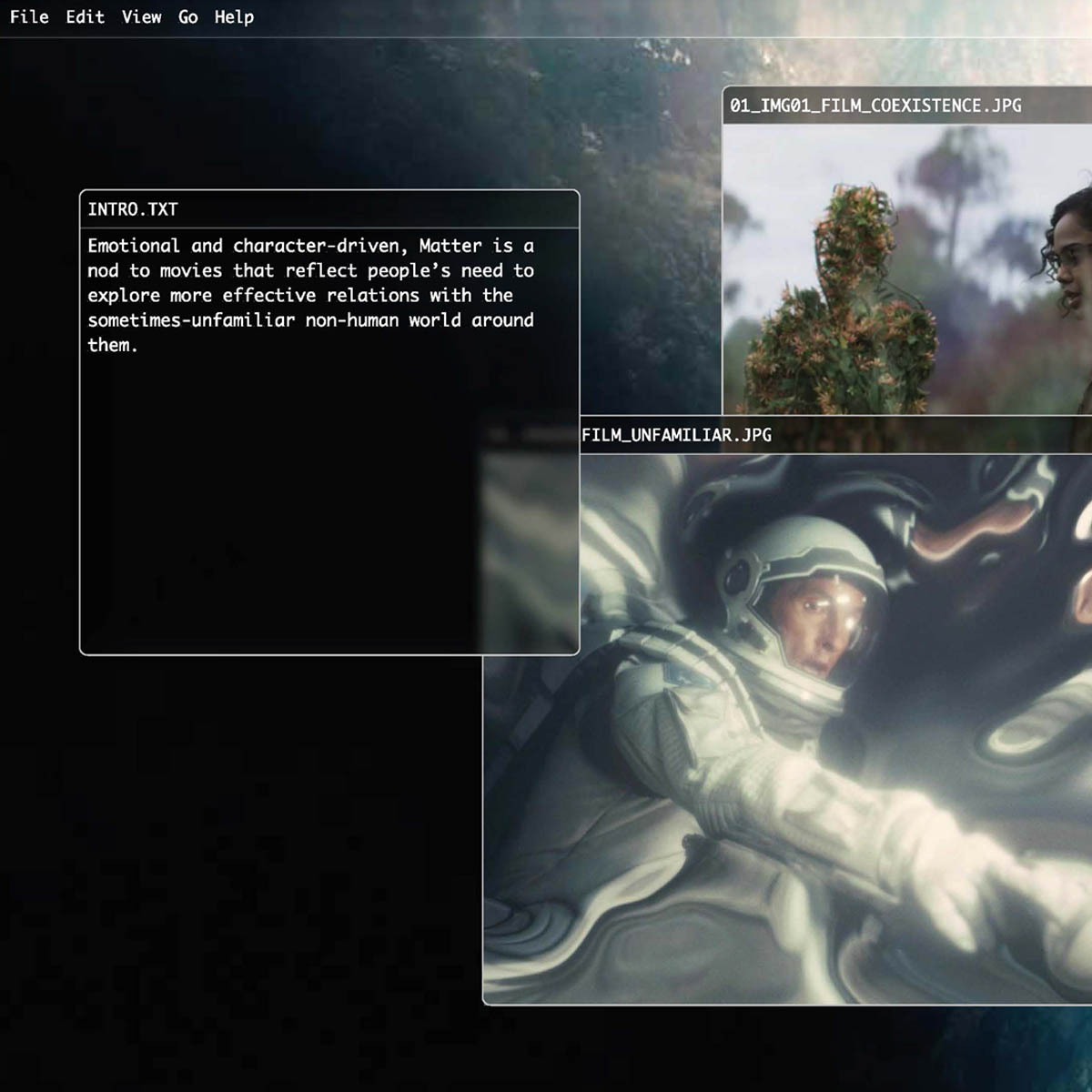

Example page from the Matter slidedeck

Example page from the Matter slidedeck

At the same time, David A. Kirby’s [3] analysis of “diegetic prototypes” – fictional technologies that influence real-world technological development – in Hollywood films such as Minority Report has been central in showing how movies function as shared spaces where scientific, technological, and public imaginations meet.

Kirby’s ideas directly inspired Julian Bleecker’s [4] notion of “design fiction”, an approach that adapts cinematic prototyping to explore and critique possible futures – and which he discusses in relation to films including 2001: A Space Odyssey, Minority Report, Jurassic Park, and Blade Runner.

At Lancaster, design fiction has been developed in work from Joseph Lindley and collaborators. Their ACM publications span prototyping inspired by Her [5], reflections on the field’s development informed by Back to the Future [6], and the use of fictional technologies inspired by Blade Runner to probe contemporary technological assumptions [7].

Taken together, these perspectives shaped my interest in experimenting with moviemaking as a design research method: not simply to imagine fictional worlds, but to use the structure of film concepts to translate academic research into narrative forms that can travel beyond traditional disciplinary boundaries.

At Design Research Works I continued to explore how design researchers might collaborate with academics from other disciplines to co-create film concepts. This opportunity took shape during the Anticipation ‘24 conference, hosted at Lancaster University, where I met an STS scholar working on an ethnography of a global nuclear-fusion development programme.

Over lunch, we discussed the Honolulu workshop, and I suggested we try turning the paper he presented at the conference into a movie concept. After the conference, I sent him the same five-slide template I had used at 4S. A few months later, he returned an early story outline, which I then expanded into a fuller narrative and world. To visualise it, I collaborated with designers Alistair Jones and Marta Puchala.

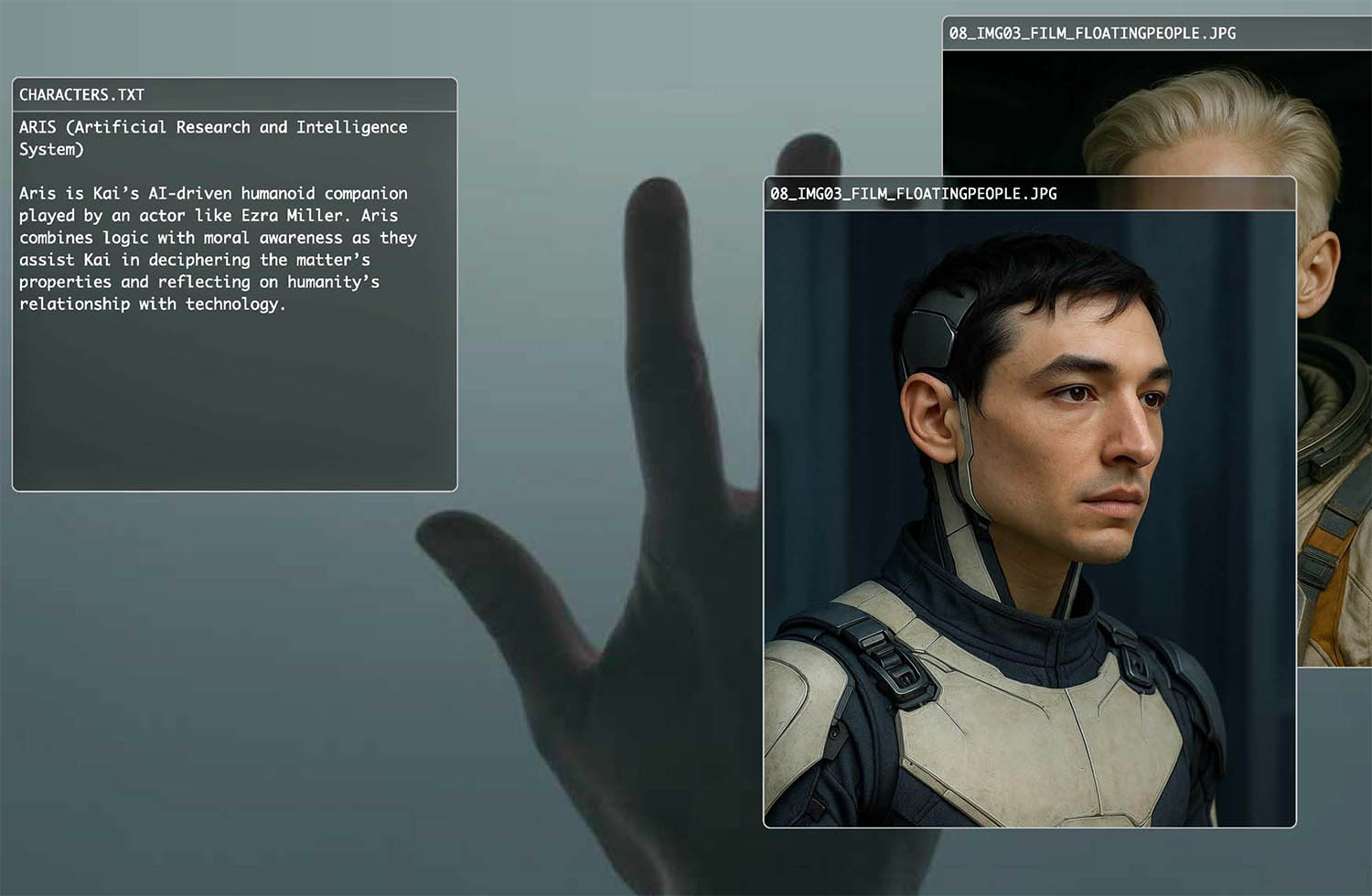

The result was Matter, a movie concept set in a future reshaped by humanity’s pursuit of limitless energy. The story centres on a mysterious substance that interferes with water at the quantum level, creating unstable and surreal ecosystems. Through this transformed world, a human space explorer, their AI-driven humanoid companion, and an enslaved cyborg-turned-philosopher navigate collapsing ecological systems, raising questions about what forms of knowledge might be needed to live with such volatile futures.

Character page from the Matter slidedeck

Character page from the Matter slidedeck

We also shared Matter with the STS scholar’s colleagues, whose feedback highlighted both its potential and its rough edges: the need for a clearer protagonist journey, a more sharply articulated STS contribution, and alternative pathways beyond a purely dystopian ending, especially if the concept is to be used in workshops or public engagement.

Developing and testing Matter during the residency showed how aspects of moviemaking can function as a design research method, opening new spaces for cross-disciplinary collaboration and conversation. It also raised ongoing questions: How might speculative film concepts like Matter be used with different audiences? What kinds of workshops could they support? And how might practices like this give rise to new forms of cross-disciplinary design research?

References

[1] Frayling, C. (1993). Research in Art and Design. Royal College of Art Research Papers.

[2] LICAatLancaster. (2013). Perspectives on Production Design. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HFZSuNdT5vo&t=4s

[3] Kirby, D. A. (2010). The Future is Now: Diegetic Prototypes and the Role of Popular Films in Generating Real-world Technological Development. Social Studies of Science.

[4] Bleecker, J. (2009). A Short Essay on Design, Science, Fact and Fiction. Available at: https://blog.nearfuturelaboratory.com/2009/03/17/design-fiction-a-short-essay-on-design-science-fact-and-fiction/

[5] Lindley, J. G., & Potts, R. (2014). A Machine. Learning: An example of HCI prototyping with design fiction. In Proceedings of the 8th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (NordiCHI ‘14).

[6] Lindley, J. G., & Coulton, P. (2015). Back to the Future: 10 Years of Design Fiction. In Proceedings of the British HCI Conference 2015.

[7] Sturdee, M., Coulton, P., Lindley, J. G., Stead, M., Akmal, H. A., & Hudson-Smith, A. (2016). Design Fiction: How to Build a Voight-Kampff Machine. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.